Build Your Exoskeleton

Personal AI workforces are forming. The question is whether you control yours.

László Moholy-Nagy’s “A19” (1927)

Last week I spoke to a clone of myself: a language model fine-tuned by friends on my public essays. I wasn’t expecting to be surprised, given how this technology is a couple of years old now, but the conversation was unlike anything I could have expected.

The clearest way to describe it was like consulting a future version of myself; ‘future-me’ who had already done the research I hadn’t gotten around to doing yet. When asked about topics I hadn’t written about, it made intellectual connections I am almost sure I’d have made myself, had I taken the time to do the research. It was rather like peering into the trajectory of my thoughts instantly, without the intermediary reasoning steps.

As a result, the thought of giving away my private messages, meeting transcripts, browsing history, and financial records is setting off some major alarm bells.

In 2000, Larry Page said that “Artificial intelligence would be the ultimate version of Google, it would understand everything on the web, it would understand exactly what you wanted, and it would give you the right thing.” Earlier this week, David Lieb, creator of Google Photos and Y Combinator partner, tweeted: “I desperately want to connect my Gmail, Calendar and Google Photos to ChatGPT so it can know my life and help me more.”

The future where we surrender our thinking to machines is here, and we’re welcoming it with open arms.

The Short Century

Back in 2019, technologist Brad Burnham outlined another vision: “My dream is to capture all of the data I create as I interact with services before it gets embedded in a server somewhere.” He suggested we could permission out this data to specialised products, like “a news reader with the benefit of knowing everything I already consumed” or “a product feed that completely changes our concept of advertising where I’m interacting on my terms.”

Since Burnham gave his speech, three key breakthroughs—vector databases, cheap embeddings, and high-quality speech-to-text models—have turned your personal data into the most valuable asset you’ll ever own. Burnham’s vision is more relevant than ever: either we own the data that fuels these systems, or we send it to companies like OpenAI, where it could be used for reasons we have little say in. [1]

Simply by interacting with software products today, you are capturing a detailed snapshot of your thinking patterns, relationships, and intellectual property. Increasingly, this data will be more useful than all your other assets combined. Your digital footprint (or soul) captures four types of data about you:

As of July 2025 in San Francisco, it has become all the rage to combine these sources with reasoning models and commodify a new super capability. Cluely’s “Cheat on Everything” AI captures your screen and lets you gain an advantage during interviews, while Clay and Pally sync your LinkedIn, WhatsApp and Gmail into one place, letting you manage your personal relationships effortlessly.

Homie, a company recently invested in by OpenAI, lets students sync less obvious data like their DoorDash activity, Spotify history, and TikTok interactions to post to friends 150 times a day on your behalf, like a more intimate and ADHD version of BeReal.

Expect the race to automate your life to be messy and divided across many competing tools in the short-run, but with time, we should anticipate our AIs as a personal workforce working together.

Personal Presidencies

Within days of winning the election, the incoming president becomes responsible for making more than 4,000 political appointments, overseeing a budget of roughly $6 trillion, and leading an organisation that employs more than four million federal employees and soldiers. This hierarchy of delegation is so vast that almost all of it can operate entirely independently of the individual in power. Instead, as with all organisations, it is designed to amplify the President’s decision-making capacity across great scales, like an exoskeleton.

If we zoom out far enough, we’re witnessing the commodification of the presidential abstraction layer. Your personal data becomes the input to a cabinet of AI ministers: chiefs of staff, therapists, coding agents, each specialised in different domains of your life, all reporting to you as Commander-in-Chief. We’ll all be the decider, and we’ll all decide what is best for ourselves.

Historically, the ability to mobilise a workforce has separated the powerful from the weak. The wealthy benefited from stronger abstractions—private tutors, employees or soldiers working on their behalf. Now, that leverage is democratising. Through products like Khan Academy and YouLearn, we’re seeing Bloom’s 2 Sigma principle in action: personalised AI tutoring that makes average students perform two standard deviations better than classroom learners. With workflow builders like Gumloop and Lindy this principle generalises to other domains.

For many of us, this might begin with a personal Jarvis like the one in this week’s assistant from ElevenLabs, capable of surfacing context from all across your Slack, Gmail, Calendar and the web. Some of us might start handing over real-time access to our financial records, our browser history, our private DMs, meeting transcripts and journal items. We’ll do this because it will feel like hiring the smartest person you know to be your executive assistant; entrusting them with all your data, throwing a budget at them, and having them turn your life into a delight.

But what still remains uncertain is the degree to which AI will feel like having your smartest friend help you make more money. Note that Tony doesn’t even consider electing Jarvis to CEO of Stark Industries in this video, instead he elects Pepper, who doesn’t ever speak to Jarvis. In reality, those who lean into AI will attain the widest advantages first; active participants will spend more time developing agentic workflows, waking up to deeply researched reports, and most effectively turn casual ideas into useful products that gain adoption.

Vibe Entrepreneurship

We’re witnessing the birth of the superhuman entrepreneur. In November 2024, coding agents got their largest update yet with the release of Anthropic’s Claude-3.5-Sonnet. Products like Lovable, v0, and Replit soon became some of the fastest-growing products ever, capable of turning an idea into a working prototype. Now, developer-centric companies like Vercel and Stripe are ‘agentifying’ their developer documentation into llm.txt files designed for LLM consumption to support “vibe coders” who rely solely on the outputs of coding agents like Claude Code, Amp and the Gemini CLI, rather than spending time in the syntax.

We’re witnessing the birth of the superhuman entrepreneur. In November 2024, coding agents got their largest update yet with the updated release of Anthropic’s Claude-3.5-Sonnet. Products like Lovable, v0, and Replit soon became some of the fastest-growing products ever, capable of turning an idea into a working prototype. Now, developer-centric companies like Vercel and Stripe are ‘agentifying’ their developer documentation into llm.txt files designed for LLM consumption to support “vibe coders” who ditch the syntax and rely solely on the outputs of coding agents like Claude Code, Amp and the Gemini CLI.

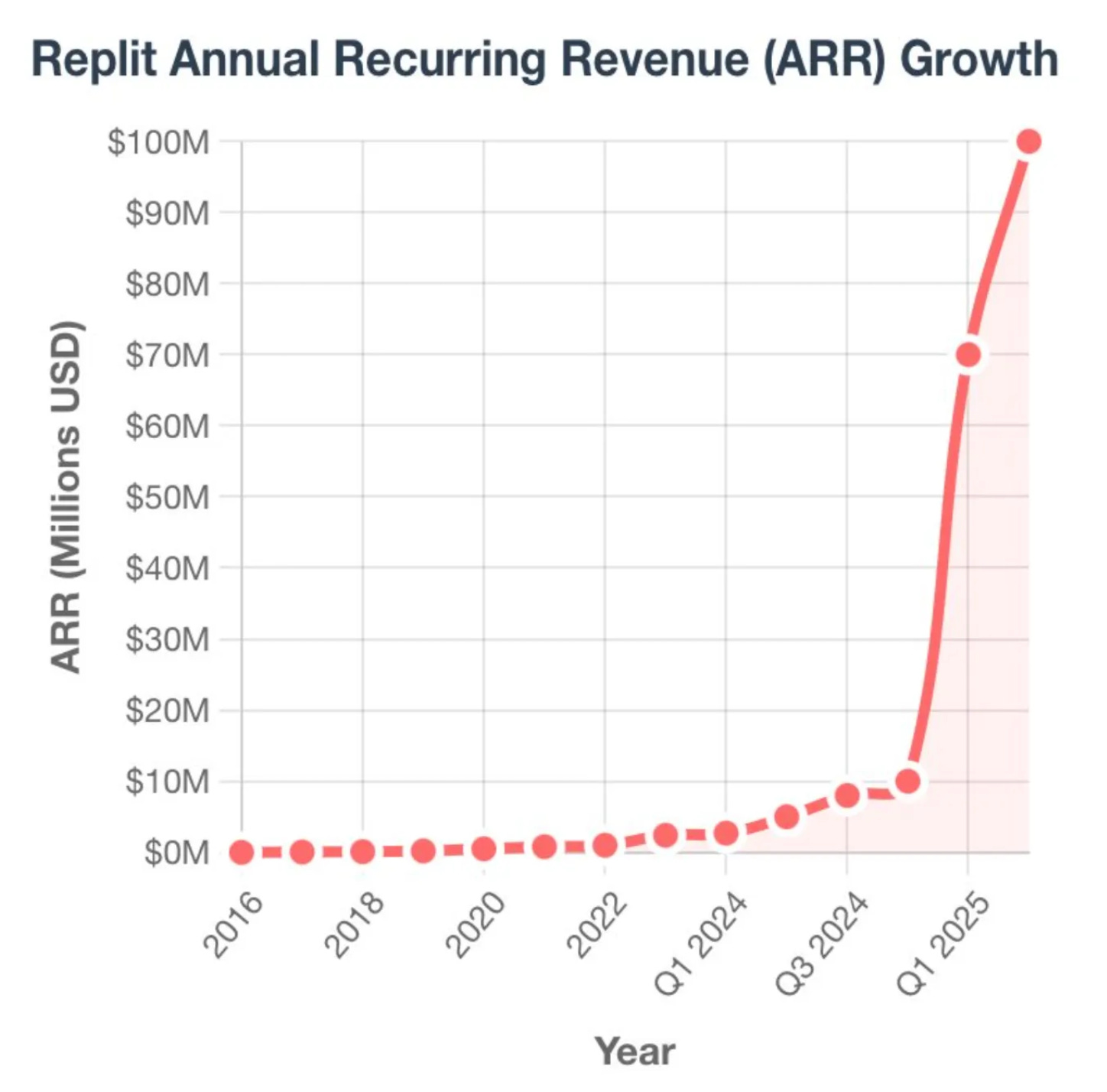

Figure 1. Replit, founded in 2016, recently experienced 10x growth in under two quarters following the release of Anthropic’s Claude-3.5-Sonnet (New)

This impact travels beyond the developer layer. Cursor hit $100m ARR with just 30 employees, while Midjourney hit $400m with just 40. Kyle Vogt, founder of The Bot Company, predicts the next $100bn company to emerge will have fewer than 100 employees. With each employee supporting revenue of $10m at companies like Windsurf, top performers are less akin to “vibe coders” and more akin to “vibe entrepreneurs”.

Startups become far more formidable when research teams can be triggered at will, epics automatically become pull requests, and you need only focus on steering. The traditional product development flow of user research → problem identification → solution design → code, has compressed into a single process. In the Autumn Y Combinator batch, one quarter of companies relied on AI for 95% of their codebase, and this number is expected to rise fast in the Summer batch.

At Real Machines, Britannio and I built Onbox.ai to sync all our transcripts, messages and code into a single repository that we can drop into AI to keep it up to date with our company. Such a system can contribute by finding important posts from the web, adding to products while we sleep, and contributing to our discussions. It could even write bespoke software to solve the problems we’re facing in real-time.

Following this trend, companies like Thinking Machines are building custom AIs that reinforcement learn to optimise KPIs, while Anthropic’s Project Vend tested Claude’s ability to independently run a retail operation in San Francisco. For the first time ever, it is possible to conceive of lights-out software development teams, running unsupervised for 30 days like the FANUC Autofactory. Imagine customer feedback channels that automatically enrich Linear tickets, trigger coding agents, and render previews for project managers to curate.

Figure 2. Project Vend tested Claude’s ability to run a small shop in San Francisco. Results are mixed for now, but the motivation is clear.

The Curse of Personal Data

What unsettled me about OscarClone wasn’t its tone, but rather the intuition inherent in its response. When asked to write about a topic I’d never publicly discussed—the optimal way of constructing a society—it recreated the result of my research process in its response using a few obscure terms I had to look up; terms I could well have stumbled across and proudly written into my own response. The AI had essentially simulated how I learn about new subjects.

This instils me with certainty that with the rest of your data, a fine-tune could crystallise how you think beyond any hope of your own comprehension. With this behaviour, a system could project your reasoning into domains you haven’t yet explored, making you very vulnerable to manipulation.

This brings us to the cursed aspect of the timeline we find ourselves in. In a world with agents running around the web on our behalf, you will need to entrust your agents with enough knowledge to ensure their responses are relevant. But by uploading your notes, messages, conversation history and transcripts into ChatGPT, you are actually handing over a map of your behaviour, your thinking patterns to a third party. This is the type of data you need only hand over once.

These properties make up Simon Willison’s “Lethal Trifecta”, which amount to the perfect information to expose you to any attacker. An AI agent with (1) Access to your private data (to act intelligently on your behalf), (2) Exposure to untrusted content (to gather information from the web), and (3) The ability to take actions in the world (and potentially leak your private data) could be tricked quite easily by a stranger into handing over that data for manipulation or blackmail.

Let us return to OscarClone, the AI finetuned on my public data. What unsettled me wasn’t its accuracy, it was its intuition. Asked to write about a topic I’d never publicly discussed (the optimal way of constructing a society), it included several interesting terms I would have discovered and proudly incorporated had I been responding myself (terms slightly out of my initial lexicon), and some of the learnings from intellectual rabbit holes I would inevitably have fallen down in my response.

I am now confident that with enough data, a finetune could crystallise how I think and the probable trajectory of my reasoning into domains I haven’t yet explored, making me very vulnerable. In a world of composite agents running around the web on our behalf, you must entrust their agents with meaningful permissions that let them externally communicate with tools and parse that information relevantly. But by uploading your notes, messages, conversation history and transcripts into ChatGPT, you are actually handing over a map of your behaviour, your thinking patterns, which ultimately would amount to your soul to a third party. This is the type of data you need only hand over once.

These properties make up Simon Willison’s “Lethal Trifecta”, which amount to the perfect information to expose you to any attacker. An AI agent with (1) Access to your private data (to act intelligently on your behalf), (2) Exposure to untrusted content (to gather information from the web), and (3) The ability to take actions in the world (and potentially leak your private data) could be tricked quite easily by a stranger into handing over that data for manipulation or blackmail.

This risk is already compounding in the arms race of TikTok, YouTube, Instagram, and many other recommendation algorithms designed to emulate your behaviour. Products optimising for attention already “strip mine” the human biological overrides for self-control. With frontier video models like Midjourney and Veo 3 cheap enough to run en masse, we are starting to explore the very best highlights of an exaggerated, unnatural world many orders of magnitude less resistible than the one we evolved in.

Companies like Artificial Societies and Palantir already run simulations of members in society, and would achieve far greater accuracy by building finetunes on publicly available data. If we refuse to regulate algorithms designed to carve away at the human cortex, society at large will not be able to resist the moloch of virtualisation.

On a positive note, until very recently, the only way to defend against the combined engineering talent of ByteDance was to delete or block the app, which has become a notably common behaviour among my peers. Instead, we can now have an AI parse the feed ahead of time with respect to what you actively chose to see. This is the promise of truly private exoskeletons; the means to decide what traps you fall into, and what behaviours you choose to foster. If your AI knows you better than TikTok, it can parse the feed more accurately and remain a strong proxy you can trust. This is a technology worth striving for.

Building Safer Exoskeletons

The uncomfortable reality is that perfect protection doesn’t exist. LLMs often cannot distinguish trusted instructions from malicious ones any more than humans can. Building an effective exoskeleton is equivalent to building a company, where one subgoal is to protect the intellectual property or internal dynamics of the organisation from leaking to competitors. If these protections fail, a single bad actor could whistleblow an operation the scale of the NSA.

For example, Apple’s Project Purple was set up to develop the iPhone without the engineers knowing the true purpose of their efforts. Two teams worked on separate products that would later be combined into a monoproject. At Tesla and X, binary watermarking is used as a “canary monitoring” technique to tag the origin of all documents, emails and conversations to ensure that if these tokens appear in unexpected context, you can trace a leak. Within the government, Special Access Programs (SAPs) control permissions at every layer of the organisation, facilitating top-level clearance at sites like Area 51.

When building digital exoskeletons, agents could be configured to use distinctive tokens, tagging their activity at a level of detail human bureaucracies aren’t able to achieve. These tokens could be permissioned such that if they appear in the wrong context, they would flag an alarm that the human can immediately check.

Post-Snowden, the NSA introduced a “Secure the Net” protocol where consequential actions required verification from multiple individuals. In the long-run, having different agents keep each other in check would be the ultimate fallback, given that this is how human society maintains order for the most part. Within organisations, manager agents vet frontline agents whenever a new task is created, and no single agent should be allowed to build emulations of the agents at higher permission levels, except under direct supervision from the human operator.

Human supervision should be expected to fill the gaps as the abstraction grows. Until an operation achieves a determined number of nines of accuracy, this should remain the case. Gradually, we should expect this level of approval to rise up Moravec’s landscape as agents become human-level-or-above at performing these tasks.

These security measures—watermarking, multi-agent verification, human oversight—assume we remain the superior decision-makers in the loop. But when agents gain sufficient adaptability, saturating tasks like ARC-AGI-3, our role as supervisors will become increasingly irrelevant and we risk becoming the limiting factor in our own exoskeletons. At this point, we will either need to upgrade our brains more qualitatively or introduce stronger mandates for human hegemony over all known organic and artificial life (given how things are going, the former is more realistic).

The real goal is to carry sentient life through the full arc of emergent complexity responsibly and avoid mass destruction along the way.

Notes

[1] A timeline of the three key breakthroughs:

- First, vector databases were developed before the AI boom. Weaviate and Pinecone built infrastructure for semantic search using early embedding models like GloVe and word2vec. When GPT-3 and RAG arrived in 2020, this database layer could scale.

- Second, on December 15, 2022, shortly after the release of ChatGPT, OpenAI released their cheap embedding model “text-embedding-ada-002”, enabling developers to index rich language data with 6x less memory storage at a 5x price reduction. Vector databases were soon integrated into thousands of products over the following 18 months.

- Third, on March 1, 2023, OpenAI’s launch of the Whisper API at $0.006 per minute created a 10x cost reduction that enabled high-quality transcription at scale. The same month, Granola was founded, and speech-to-voice companies like AssemblyAI and DeepGram reported customer growth of greater than 200% by the end of the year. High fidelity transcription allows us to capture much of the high quality data we’ve never previously captured.